Facebooktwitteremailmore Artemisia Gentileschi the Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art

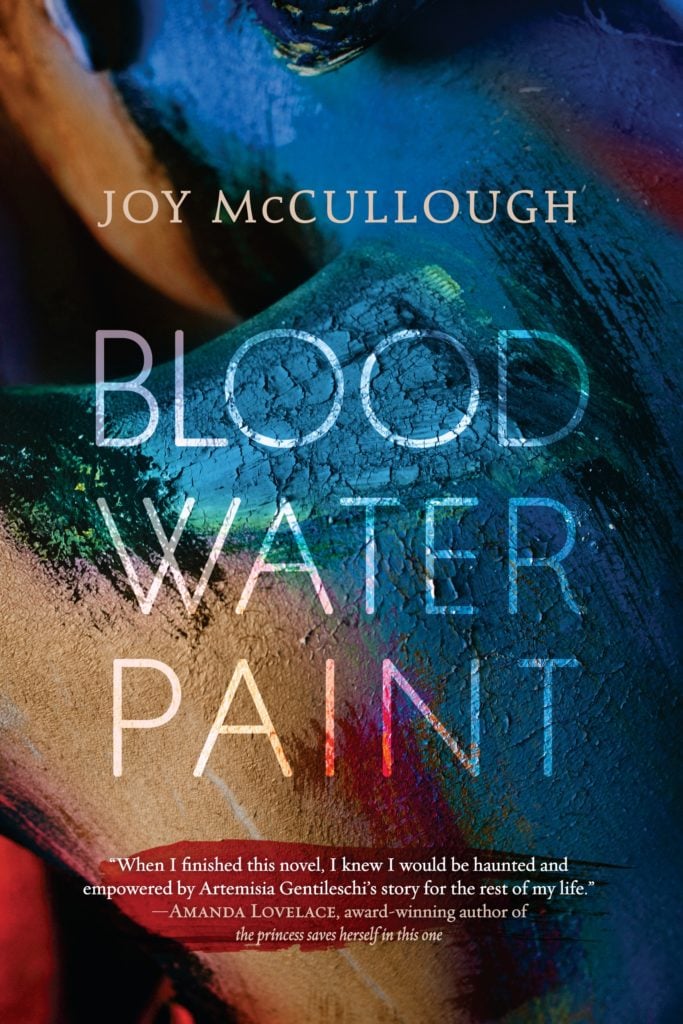

In Blood H2o Paint, author Joy McCullough tells a tragic yet empowering tale about Artemisia Gentileschi, the 17th-century Italian Bizarre painter. Gentileschi has gone down in history non only every bit an acclaimed Old Primary painter, but too a feminist hero who successfully pressed charges against her teacher, artist Agostino Tassi, who was convicted of raping Gentileschi in 1612.

Because a woman couldn't bring rape charges at the time, her father, the noted painter Orazio Gentileschi, filed the lawsuit. It was considered a crime of belongings damage; Artemisia had lost "bartering value."

During Tassi's seven-month trial, midwives physically examined Gentileschi in front end of a judge, who and then demanded that her easily be tortured in social club to run into if she inverse her story under force per unit area. The saga is meticulously documented in some 300 pages of court records, which McCullough mined beginning for a play and then for the novel, an emotionally resonant tale written entirely in free poesy.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders (1610–11). Courtesy of the Schloss Weißenstein collection, Pommersfelden, Germany.

Gentileshchi, who was just 17 at the time, refused to permit the ordeal define her. When her hands healed, she joined the Accademia di Arte del Disegno Florence—becoming the offset woman to nourish—and painted for patrons in Venice, Naples, and London, where she was sought out by King Charles I. Essentially illiterate, Gentileschi told her story through her art, painting several works that depicted brutal violence, such as Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–20).

After her expiry, Gentileschi roughshod into obscurity, merely her accomplishments have been recognized in recent decades. As an creative person, she is considered something of a female Caravaggio, who was a shut friend of her begetter.

Gentileschi set a new auction record this past December, with the $two.2 million auction ofSainte Catherine d'Alexandrie at Christophe Joron-Derem to London's Robilant + Voena gallery, according to the artnet Price Database. This newly discovered self-portrait, showing the creative person in the office of the martyr St. Catherine, bested her previous record, Mary Magdalene In Ecstasy, which sold for $one.2 million at Sotheby'due south Paris in 2014.

artnet news spoke with McCullough virtually Gentileschi's relevance in 2018 and how her work has transcended her personal tragedy.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes (c. 1614–1620). Courtesy of the National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples.

When did you lot get-go learn about Artemisia, and what was your reaction to learning her story?

There was a passing reference to Artemisia in a Margaret Atwood book I was reading. I was curious, and then I went looking, and ended up in the fine art history department of the library. I was outraged that I'd never heard of her before. Both her art and her story felt like things I should have learned in schoolhouse. That was in 2001.

The idea for this volume long predates #MeToo. What inspired you to begin researching the play that evolved intoClaret H2o Paint? What was the conversation about sexual assail like at that time?

As soon as I discovered Artemisia'southward story, I knew I was writing a play nearly information technology. Information technology had a very long development process before information technology was finally produced in 2015 in Seattle.

Back in 2001, at that place wasn't any sort of conversation [around sexual violence] like there is now. There were conversations in my women'southward study classes, or inMs. magazine, or privately among my friends. Today, the internet, as horrible equally it can be for women, has facilitated these conversations, and has been empowering in terms of sharing stories.

What was it similar reading the courtroom transcripts of Artemisia'south case?

I read the English language translation of the complete transcript of the trial in Mary D. Garrard'southArtemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Fine art (Princeton University Printing, 1989). Information technology was immediately engaging and also horrifying to run into how identical this rape trial from 400 years agone was to a rape trial then in 2001—and now, considering it never changes.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Sainte Catherine d'Alexandrie. Courtesy of Robilant + Voena.

Based on how the trial is portrayed in your book, I saw some very uncomfortable parallels to how say-so figures care for sexual assault claims in the present day.

The transcript is really interesting, because it is not only focused on the day of the assault. It gives the whole context for her relationship with this man. The testimony is filled with the same kind of slut-shaming and victim-blaming that we still see today. At one point, the rapist's side presents letters that they claimed Artemisia had written to all these other lovers. But she was illiterate, she couldn't write!

The idea was, "we're going to say she was a whore, so obviously she wasn't raped." That'due south a story that nosotros tell at present: "How many men take you slept with? Were you a virgin? What were y'all wearing?" It's all just fierce the victim down, which was not happening to the rapist. He is just causeless to be an upstanding man.

And Tassi was anything but! He was married and had mayhap hired bandits to kill his wife!

Yep, he had a very shady and sordid by.

That doesn't come up across in the novel.

That was intentional. So often, there'due south this narrative that you can tell that rapists are bad guys—that guy's creepy, that guy's rapey. But they're not. They tin can be captain of the football team, a completely upstanding, quality guy from the exterior. I didn't want Agostino to be plain shady. I wanted it to reflect the more complicated reality that exists in and then many cases.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Magdalene. Courtesy of Sotheby'southward.

When I was reading it, I really thought it was a beloved story for the first half of the volume.

That's what I wanted—and that's what she wanted. Artemisia was falling for Tassi. She idea they could have something, just when she wouldn't give him what he wanted, it turned.

In the book, Artemisia wants naught to practice with Tassi later on the rape. But in the trial, it's clear that she continued to hope that they would marry. Why did you brand that change?

That was something I didn't desire to include in the book. It's so offensive to our modern sensibilities that someone would desire to marry their rapist, merely it was non uncommon back and then. Once a adult female had been raped, she was no good as a bride, then marrying the rapist was a manner of making the best of a bad situation.

Why did the courtroom resort to torturing Artemisia?

We can ask that same question of rape trials today! Why are the victims forced to prove over and over again that they're telling the truth? A adult female'due south word is worth less than that of a man. Even today it still takes the word of dozens of women earlier a effigy like Harvey Weinstein or Bill Cosby will fall from grace. The torture was to evidence her word was good. As a homo, Agostino Tassi didn't accept to bear witness his word was proficient.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Danaë (1612). Courtesy of the St. Louis Fine art Museum.

How much of Artemisia's personality were you lot able to discern from the records, and how much is your ain interpretation?

It's definitely a work of fiction, and I created a character. From this menses in her life, all we have to speak for her is her art—which I think says a lot—and this trial transcript. Anyone who's been through a trauma wouldn't desire y'all to judge them entirely based on that piece of their life, but there are seeds in the transcript that I congenital from.

When they're preparing to torture her and they're weaving these cords around her knuckles to beat out her joints, Artemisia looks at her rapist and she says "this is the ring y'all requite me, and these are your promises." He said he'd marry her, and then he backed out. And as they're torturing her, she says "Information technology's true, information technology's true!" The transcript notes that she repeats it over and over—they couldn't even write it in every bit many times equally she said it. I run across this burn in her, this unwilingness to be moved in her truth. That's what I establish in the historical record, and I congenital the rest of her personality around that.

Joy McCullough, author of Blood Water Paint. Photo courtesy of John Ulman.

Why did you write the book in poesy?

Verse strips everything else abroad except the emotional core of the story. In a story like this, information technology'southward less traumatic, both to read it and to write it, when those details aren't fully described. When a historical novel that goes into all the detail of solar day-to-twenty-four hours life, almost what they wore and how they cooked, it tin can keep the reader at arm's length. Writing in poesy makes the story feel more relevant, and that was important to me, because the story is so now.

In your telling, Artemisia and her father, Orazio Gentileschi, have a fraught but ultimately, I think, loving relationship. How did you decide on their dynamic?

Information technology's such a brutal story that it needs to have bits of hopes in it. Giving Artemisia this not completely awful human relationship with her father is 1 of the ways that I did that. Orazio fabricated some horrible choices. In that solar day, yous did not leave a young unmarried adult female alone with a homo who was not family. He had to have had some cognition of what could happen when he hired Tassi. Orazio also used his daughter equally a nude model, because information technology was illegal to hire nude models in Rome. Information technology makes me cringe horribly for her.

Simply the most significant thing to me in their human relationship is that Orazio takes Artemisia on as an apprentice. He doesn't only continue her doing grunt work grinding pigments and cleaning brushes—he teaches her to a level of mastery, which he did not take to do, and was extremely unusual for the day.

Joy McCullough, Claret Water Paint, a new book most Artemisia Gentileshi. Image courtesy of Dutton Books.

In the book, you advise that Orazio was actually quite a mediocre painter, and that much of his output can be attributed to Artemisia. Is that what art historians believe? Or is that a bit of creative license?

Orazio had important commissions and his work is in major museums. In the book, she'due south a teenager who's resenting her father, so we're seeing him through that lens. It's not fair to say he's mediocre, simply there is scholarship that suggests that she contributed heavily to his work. There are paintings attributed to Orazio that Artemisia may have been responsible for. It wasn't unusual at the fourth dimension for an amateur to do uncredited work on paintings that masters would sign their names to, but I call up the lines were blurrier with the two of them.

What is the significance of the intertwining stories of the biblical figures Judith and Susanna who appear in the book?

Artemisia's female parent died when she was 12. In the book I've given her Judith and Susanna. They were figments of her imagination, they weren't actually there—just she was painting them. She was throwing herself into her work and that was how she got through it, and that was how she gave herself women to rely on and look up to and believe in.

When I outset discovered Artemisia's story, I likewise learned about Judith and Susanna's for the first fourth dimension. During the Reformation, Protestant scholars decided that certain stories were not divinely inspired, and then they were removed from the Bible. It's no big shocker to me that these stories of powerful women were alleged apocryphal. Stories are powerful, and Artemisia draws strength from Judith and Susanna'due south stories.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders (1622). Courtesy of the collection of the Marquess of Exeter, Burghley House, Stamford, Lincolnshire, England.

Do you think Artemisia'south artistic achievements accept been overshadowed by her rape? What became of her afterward the trial?

Artemisia did recover from her torture, and virtually a calendar month after the trial she was married off to a friend of a friend and moved to Florence. She went on to flourish and have a wonderful career. I could write a whole series of books virtually information technology. This episode from her life was what spoke to me because I was so gripped by the court transcripts and how little things take changed. I was inspired past the magnitude of the horror Artemisia survived before going on to have this amazing career.

Why do yous think Artemisia was able to succeed every bit an artist in an era where at that place were then few options for women?

She didn't have much privilege, merely her father was a painter and a colleague of Caravaggio's. Orazio was willing to take her on as an apprentice and to teach her. Just that wouldn't have been plenty on its own. Artemisia had this sheer force of will, this drive that female artists have had to have throughout history in order to go out their marker.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, heart-opening interviews, and incisive disquisitional takes that drive the conversation forwards.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/a-new-novel-artemisia-gentileschi-1255694

0 Response to "Facebooktwitteremailmore Artemisia Gentileschi the Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art"

Post a Comment